Jeff Morris creates experiences that pop audiences’ minds out of the ordinary, to realize new things about the sounds, technology, and culture around them. His performances, installations, lectures, and writings appear in international venues known for cutting-edge arts and for asking deep questions in the arts. He has won awards for making art emerge from unusual situations: music tailored to architecture and cityscapes, performance art for the radio, and serious concert music for toy piano, slide whistle, robot, Sudoku puzzles, and paranormal electronic voice phenomena.

He has presented work in the Onassis Cultural Center (Athens), Triennale Museum (Milan), D-22 (Beijing’s avant-garde music scene), the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library and Museum (Austin), the Chicago Architecture Foundation’s “Open House Chicago,” and the Boston Microtonal Society, and won awards in the Concours de Bourges (France), Viseu Rural 2.0 (Portugal), “Music in Architecture” International Competition (Austin), the Un“Cage”d Toy Piano Competition (NYC), and the “Radio Killed the Video Star” Competition (NYC). Jeff’s writings that explore the aesthetic questions raised by his music have appeared at the International Symposium on Electronic Art, International Computer Music Conference, Generative Art International Conference, and Computer Art Congress, as well as in publications by Leonardo Music Journal, Springer, and IGI Global.

Today, Jeff is our featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our artists. Read on to hear about a particularly cheesy situation Jeff was in during an artist residency…

Who were your first favorite artists growing up?

My earliest musical memories are conducting along with the Boston Pops Orchestra with John Williams on PBS television and also picking out melodies on my toy piano along with The Rock-afire Explosion—that was the animatronic cover band at Showbiz Pizza Place. Later, I got into Bach’s organ music and Harry James’s big band (he started with Benny Goodman, and he later gave Frank Sinatra his big break). In college, I was most at home with Thelonious Monk and Conlon Nancarrow.

What was the most unusual thing that happened to you during a performance?

Hmmm, my work often leads to unusual situations. At an artist residency in a rural Sardinian monastery last summer (through Becomebecome), I had been trying to simplify: focus on the one piece I had planned. But the afternoon before the show, the artists did a daydreaming exercise together. Mine involved a closeup view of a mouth slowly chewing. Doing an additional piece was the last thing on my mind, but as the others in my group shared their responses, it came to me! I did some coding after dinner inspired by the cable TV glitch in our hotel lobby. The hosts arranged cheeses for lunch. My new friend there, visual artist Orlando Saverino-Loeb, had experience as a cheesemonger…and a striking mustache. In an unused spot in the monastery, Orlando chewed for a long time while I shaped the audio and video live, squatting beside the laptop, in one take, during lunch. The awkward, haphazard elements delighted me. At the show, some local kids even phoned someone to translate so I could answer their questions. Don’t try it at home though, kids: Orlando almost heaved when we finished. Turns out, cheese just doesn’t work that way…

If you could spend creative time anywhere in the world, where would it be and why?

If I lived close to the Fort Worth Water Gardens, I’d be working there every day. It’s a large downtown plaza with a variety of architectural interactions among concrete, plants, and water. In different places, the water is silent or it’s roaring, in still pools, vertical sheets, sprays, or whirlpools. The concrete keeps making you ask, “Am I supposed to walk here or not? or should I climb? or sit? or just gaze?” Its diverse moods, textures, and viewing angles and its overall confusingness are invigorating and inspiring.

If you could instantly have expertise performing one instrument, what instrument would that be?

Pass. Well, it might be of utilitarian value, but as soon as you define expertise, you’re also defining what improper technique is. Then you miss out on the full potential of all the “wrong” ways to use it beautifully—I’m striving to master THAT.

What was your favorite musical moment on the album?

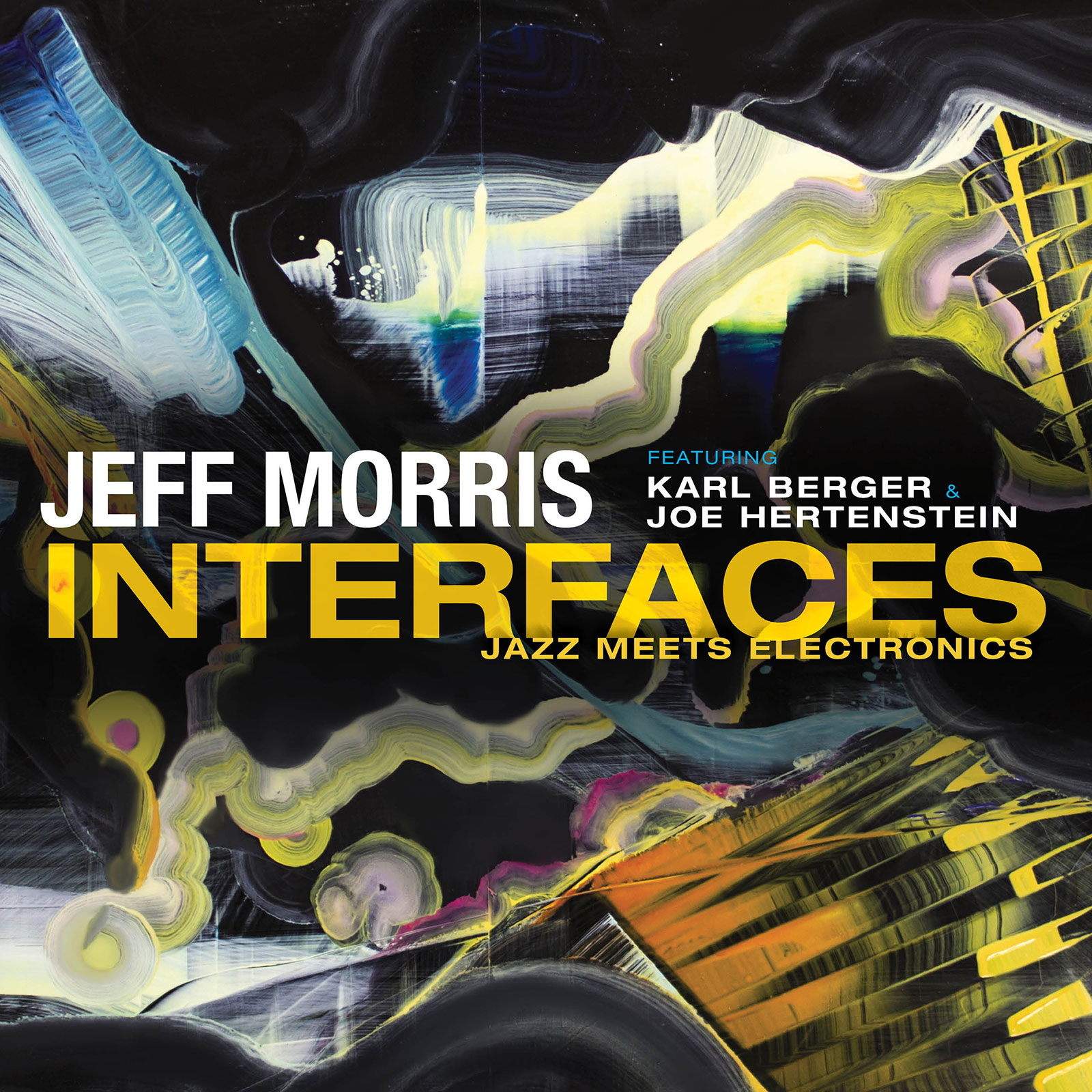

With the way I go about making music happen, it ends up full of delightful surprises, especially when I’m working with adventurous musicians like Karl Berger and Joe Hertenstein. Karl is an award-winning improviser with a long, amazing career, including founding the Creative Music Studio with Ornette Coleman and Ingrid Sertso. Joe is one of the most diversely busy and creative musicians in New York City today. In my live sampling work, I rarely write specific notes to play. Instead, I build performance situations, environments, and predicaments through the prompts I give performers and the software I write to interact with them. It’s a crucible of performance that supercharges each performer’s unique personality. It evokes musical moments that none of us would have conceived on our own.

Okay, more specifically, I’m tickled how the endings and beginnings of adjacent tracks fit together, even though they weren’t planned that way. I also love the super busy but cohesive moments where each of us seems to have found swing in parallel timelines that seem indifferent but still jam together—like one minute into the first track, Upzy. It’s a kind of meta-counterpoint at those times.

Is there a specific feeling that you would like communicated to audiences in this work?

Stay engaged with us in the performance! A lot of music we hear every day is like a foot rub: it’s done to you while you sit there passively or do other things. Sometimes music can be a trip to the gym—difficult and challenging but a chance to grow, if you’re up for it. This album is like a vigorous hike exploring unfamiliar territory to find whatever we might discover! Stay alert, guess what’s next, and question what’s going on, where each sound is coming from: “Is it Live or Is It Memorex?” And when you hear something that’s an electronic sample of something acoustic you heard earlier—or if you’re not sure whether it is or not—what do you feel? How does it change your connection to the performers? Now that technology is inserted into so many human-to-human interactions, it’s more important than ever to feel how technology is shaping our lives, the ways in which we go about being humans.

Jeff Morris creates musical experiences that engage audiences’ minds with their surroundings. His performances, installations, lectures, and writings appear in international venues known for cutting-edge arts and deep questions in the arts. He has won awards for making art emerge from unusual situations: music tailored to architecture and cityscapes, performance art for the radio, and serious concert music for toy piano, robot, Sudoku puzzles, paranormal electronic voice phenomena, and live coding using algebra and breath-controlled piano.