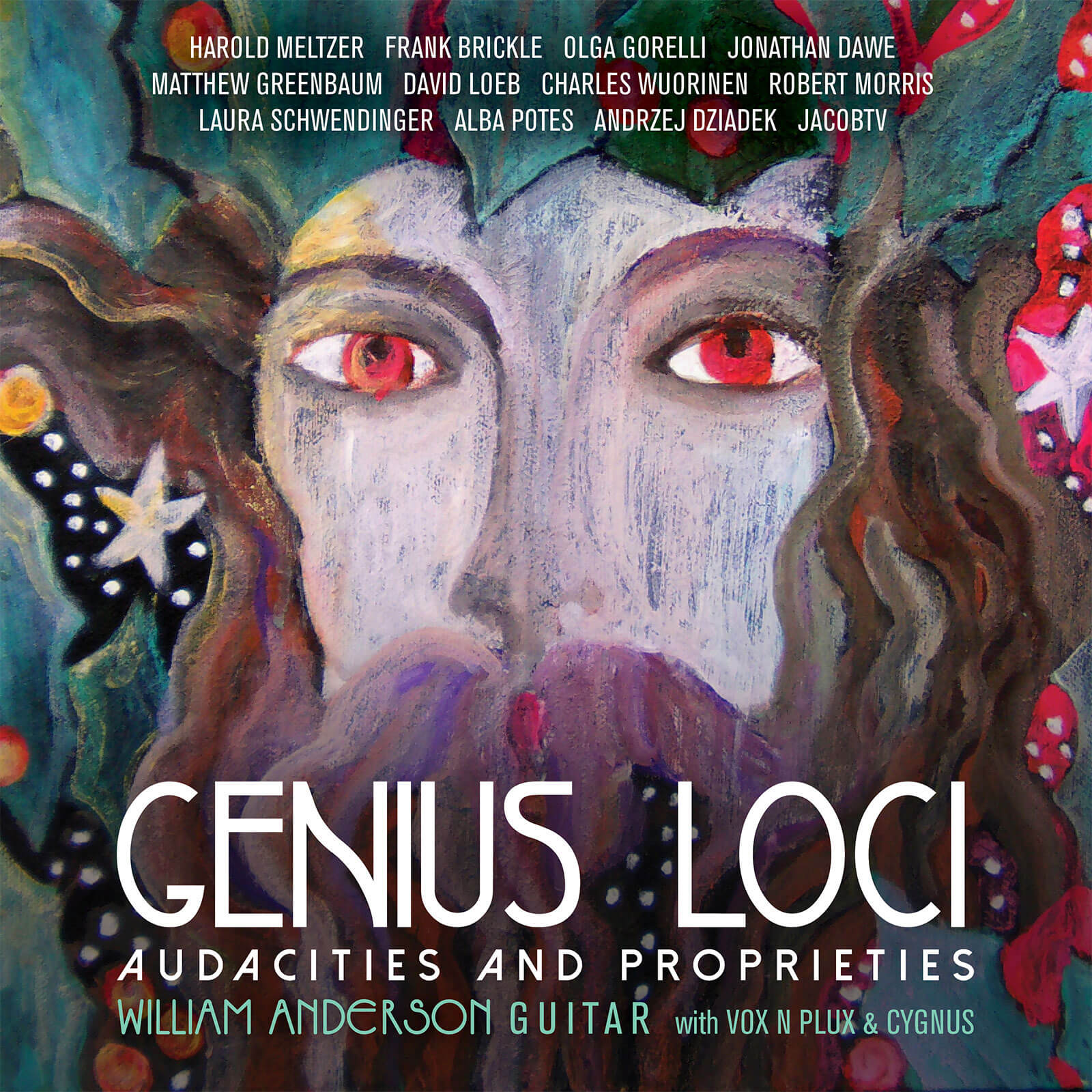

Genius Loci

William Anderson guitar

Harold Meltzer composer

Frank Brickle composer

Olga Gorelli composer

Jonathan Dawe composer

Matthew Greenbaum composer

David Loeb composer

Charles Wuorinen composer

Robert Morris composer

Laura Schwendinger composer

Alba Potes composer

Andrzej Dziadek composer

JacobTV composer

Guitarist William Anderson presents GENIUS LOCI, an anthology compilation highlighting his storied career as both a composer and a performer. The album features Anderson’s work with a variety of ensembles as well as his solo guitar music. The New York Times has deemed Anderson “the alert guitarist,” and with good reason; his playing reveals his passionate attention to detail. Anderson was mentored in the musical values of late Modernism, but now seeks compelling music without strictly aligning himself with particular aesthetic ideologies. The resulting anthology from Ravello Records captures the color and breadth of Anderson’s more-than three decades in the music industry.

Listen

Stream/Buy

Choose your platform

Track Listing & Credits

| # | Title | Composer | Performer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Doria Pamphili | Harold Meltzer | William Anderson, guitar | 3:48 |

| 02 | Genius Loci | Frank Brickle | William Anderson, mandolin; Oren Fader, guitar | 1:27 |

| 03 | Silent Moon | Olga Gorelli | William Anderson, guitar; Marc Wolf, guitar | 1:18 |

| 04 | Braggadocio | Jonathan Dawe | William Anderson, guitar | 5:01 |

| 05 | Doctor Greenbaum's Coranto | Matthew Greenbaum | William Anderson, guitar | 2:44 |

| 06 | Hail Wind: I. Moderato | David Loeb | Sheer Pluck | William Anderson, conductor; Kyle Miller, Murad Samoon, Jonathan Ramirez, Pablo Sanchez, John Coughlin, Ebin Samuel, Austin Tobia, Xavier Paez Haubold - Guitars | 2:36 |

| 07 | Hail Wind: II. Allegro | David Loeb | Sheer Pluck | William Anderson, conductor; Kyle Miller, Murad Samoon, Jonathan Ramirez, Pablo Sanchez, John Coughlin, Ebin Samuel, Austin Tobia, Xavier Paez Haubold - Guitars | 2:40 |

| 08 | Variations on "Long Ago and Far Away": I. | William Anderson | William Anderson, guitar | 2:10 |

| 09 | Variations on "Long Ago and Far Away": II. | William Anderson | William Anderson, guitar | 1:34 |

| 10 | Variations on "Long Ago and Far Away": III. | William Anderson | William Anderson, guitar | 2:07 |

| 11 | Variations on "Long Ago and Far Away": IV. | William Anderson | William Anderson, guitar | 1:22 |

| 12 | Hexadactyl | Charles Wuorinen | William Anderson, guitar | 2:51 |

| 13 | Après vous | Robert Morris | William Anderson, guitar | 10:59 |

| 14 | Footfalls | Laura Schwendinger | Cygnus | James Baker, conductor; Tara Helen O’Connor, flute; James Austin Smith, oboe; Calvin Wiersma, violin; Susannah Chapman, cello; Oren Fader, guitar; William Anderson, mandolin and guitar | 12:40 |

| 15 | Horizontes (Excerpts): No. 2, Cuando las olas con suavidad suspiran [Live] | Alba Potes | Vox n Plux | Elizabeth Farnum, soprano; William Anderson, tiple | 2:04 |

| 16 | Horizontes (Excerpts): No. 3, Calma mi niño [Live] | Alba Potes | Vox n Plux | Elizabeth Farnum, soprano; William Anderson, tiple; Oren Fader, guitar | 3:35 |

| 17 | The Song | Andrzej Dziadek | William Anderson, guitar | 6:00 |

| 18 | Postnuclearwinterscenario | JacobTV | William Anderson, guitar | 7:25 |

Cover art Holly King by Cinzia Bauci

Liner notes edited by Martha Trachtenberg

This album was a project of Marsyas Productions

TRACK 1 — Recorded Fall, 2019 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marsyas Productions

Recording Session Engineer William Anderson

TRACK 2 — Recorded 2010 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Recording Session Producer & Engineer Jeremy Tressler

TRACK 3 — Recorded 1999 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marc Wolf and Jeremy Tressler

Recording Session Engineer Jeremy Tressler

TRACK 4 — Recorded Fall, 2019 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marc Wolf

Recording Session Engineer Jeremy Tressler

TRACK 5 — Recorded Fall, 2019 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marsyas Productions

Recording Session Engineer William Anderson

TRACKS 6-7 — Recorded April 25, 2019 at the Aaron Copland School of Music

Producer Marsyas Productions

Recording Session Engineer William Anderson

TRACKS 8-11 — Recorded 1999 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marc Wolf and Jeremy Tressler

Recording Session Engineer Jeremy Tressler

TRACK 12 – Recorded 2008 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marsyas Productions and Jeremy Tressler

Recording Session Engineer Jeremy Tressler

TRACK 13 – Recorded 2019 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marsyas Productions and Jeremy Tressler

Recording Session Engineer Jeremy Tressler

TRACK 14 — Recorded March 2019 at University of Wisconsin, Madison WI

Producer Marsyas Productions and University of Wisconsin, Madison, Music Department

Recording Session Engineer Lance Ketterer

TRACKS 15-16 — Produced by Las Américas en Concierto

Recorded live on May 30, 2017 at the Church of St. Luke in the Fields, New York NY

Sound Engineer Scott Friedlander

TRACK 17 — Recorded 2019 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marsyas Productions and Jeremy Tressler

Recording Session Engineer Jeremy Tressler

TRACK 18 — Recorded 2019 at Dreamflower Studio, Bronxville NY

Producer Marsyas Productions and Jeremy Tressler

Recording Session Engineer Jeremy Tressler

Post-production (tracks 1-14, 17-18) Jeremy Tressler

Executive Producer Bob Lord

Executive A&R Sam Renshaw

A&R Director Brandon MacNeil

A&R Mike Juozokas

VP, Audio Production Jeff LeRoy

Audio Director Lucas Paquette

VP, Design & Marketing Brett Picknell

Art Director Ryan Harrison

Design Edward A. Fleming

Publicity Patrick Niland, Sara Warner

Artist Information

William Anderson

Composer and guitarist William Kentner Anderson began playing chamber music at the Tanglewood Festival at age 19. He later performed with the Metropolitan Opera Chamber Players, Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, NY Philharmonic, and many other NYC-based ensembles and organizations. Anderson was recently featured at the Festival Internacional Camarata 21 in Xalapa, Vera Cruz, Mexico, Ebb & Flow Arts in Maui, and Moderne Mandag in Copenhagen and was a member of the Theater Chamber Players, the resident ensemble at the Kennedy Center in Washington DC.

Notes

II

Cuando las olas con suavidad suspiran

cuando los rayos del sol mueren;

cuando las sombras de la noche caen

Campanas de las tarde llaman,

Margarita! Margarita!

pienso en ti!

pienso en ti!

II

When the waves softly sigh,

When the sunbeams die,

When the night shadows fall,

Evening bells call,

Margarita! Margarita!

I think of thee!

I think of thee!

— Charles Ives, translation by Alba Potes

III

Calma mi niño, duérmete

tú y yo cantaremos suavemente

que nada enturbie tu sueño

Lento el verano se está yendo

los vientos del otoño cantan

que nada enturbie tu sueño

los brillos de los sauces tiemblan

fluye el río en calma y así

fluirá el amor siempre.

III

Hush thee, dear child, to slumbers

We will sing softest numbers

Naught thy sleeping encumbers

Summer is slowly dying

Autumnal winds are sighing

faded leaflets are flying

Brightly the willows quiver

Peacefully flows the river

So shall love flow forever.

— Augusta Ives, translation by Alba Potes

“The alert guitarist.” – Paul Griffiths, New York Times

I try to be on the alert for compelling musical premises, beautifully executed. After over three decades of working with composers in the trenches, I find myself alert to the bigger picture; I see musical problems relating to bigger problems—industrialization and its stultifying business models.

My fingers on the guitar feel for the essence of each composer, like taking in the lines of an interesting or beautiful face. My fingers discover the surprising and brilliant ways the composers first make things work and then work up to something extraordinary. They do things differently than I would. They do things I would not do. My fingers explore, discover, and celebrate the “not me.”

While I was born and mentored into late and ripe modernism, I can hardly be called a modernist. Is there a name for the music here? Without a name, nothing can be replicated ad nauseam to serve a business model. Lacking a name helps keep the composers sane. It’s only bad for marketing. I’m on the alert for a more sustainable creative environment that resists the tyrannies of business models.

To quote Wendell Berry from Life Is a Miracle: Industrial business models “aspire to big answers that will make headlines, money, and promotions…for answers that are uniform and universal—the same styles, explanations, routines, tools, methods, models, beliefs, amusements, etc., for everybody everywhere.” Musical entrenchment and other discontents relate directly to the problems of propriety and sustainability that Wendell Berry brings to our attention.

20th-Century composers developed an unwholesome appetite for revolutions. For example, after some resistance, I came to have great respect for the minimalist pioneers. Their revolution was necessary and laudable, but it became industrialized. Revolutions can become a cult of the large. They can stoke our appetite for grandiosity, creating a dynamic in which, if you don’t create a revolution, you’re irrelevant. Doesn’t the moment call for another orientation no less ambitious—Haydnesque craftsmanship?

I have assembled 12 composers here, establishing a force for the small, joining Wendell Berry and his Locovores. We’re with John Dewey and his Pragmatists, who, over 100 years ago, called for creative forces to serve a specific moment, then disappear.

There is a time and place for everything, including revolution. What is a century of musical revolutions without integration?

This collection makes me absolutely joyous. It honors a great diversity of musical assets that had previously been sequestered into revolutionary camps. I am inviting you to join me in the release of those assets for purposes beyond revolution. Music is a response to our desires. It can keep us whole.

I am a guitarist/composer working with a group of ambitious, hard-working composers. We are pushing and pulling one another in various ways that further creativity. We are at peace with our considerable diversity of creative frameworks, even when those can be at odds with one another. We’re on the move. We don’t stay in one place.

We want for nothing now, except you.

— William Anderson, April 7, 2021

Videos

William Anderson at the Brno Guitar Festival, Czech Republic, August, 2011 – Bragadoccio