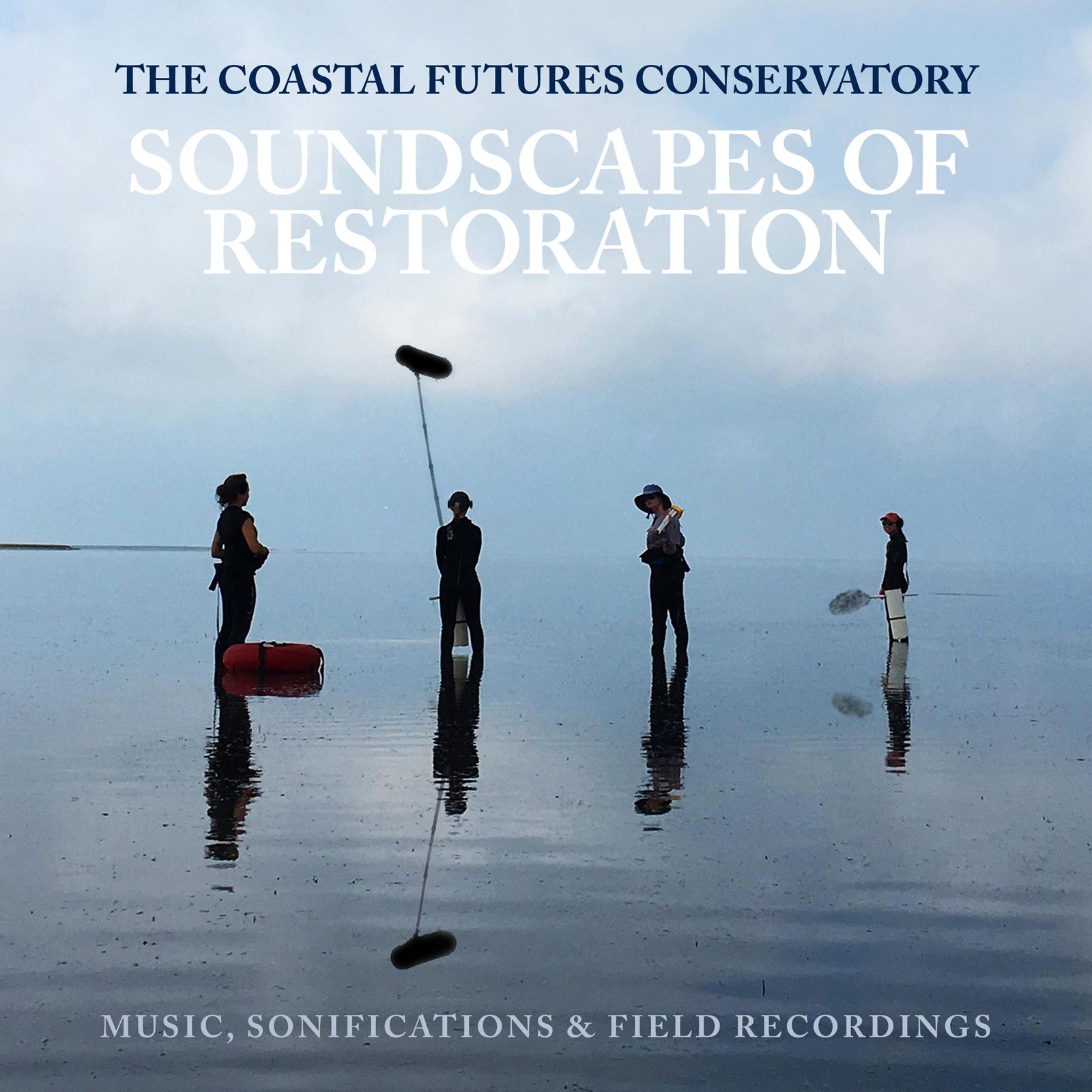

SOUNDSCAPES OF RESTORATION from composer Matthew Burtner is both an exploration and a reflection, a listening experience that leaves one changed with the desire to make change further. It is a journey that cannot, and should not, be forgotten.

Today, Matthew is our featured artist in “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to learn how growing up in Alaska influenced Matthew’s music and ties to nature, and how he came to form his non-profit organization EcoSono.

What was it like growing up in Alaska? How did this life experience influence you as an artist?

In art, like in nature, sometimes we need to settle into the biting cold to experience the inner warmth of beauty. Growing up, my family lived closely with nature in remote locations, often even without electricity or running water. Alaska can be at once devastatingly beautiful and inhospitable – the beauty often comes at the price of discomfort and even danger. Growing up here gave me a feeling of humility about our precarious existence on this planet. An aesthetic of cold naturalism pervades my music and I love to compose hard soundscapes that yield beautiful discoveries through sustained listening.

What advice would you give to your younger self if given the chance?

My advice would probably be meaningless. Being lost and taking risks is part of the process. In addition to that reminder, I would advise to keep writing simple melodies, and keep making extreme noise.

How did you come to form EcoSono?

EcoSono is a non-profit organization promoting a naturalist sound philosophy. I started developing ecoacoustic music in the 1990s as a methodology to compose nature-based music, using techniques from science and technology applied to music theory. I teach those techniques now at the University of Virginia and through the Coastal Conservatory, and EcoSono is the public engagement arm of that work. EcoSono is a nexus for like-minded sound artists from around the world to form a community around ecoacoustics.

EcoSono formed in 2009 for the publication of “Signal Ruins,” and it achieved non-profit status some years later. The EcoSono Ensemble formed for the premiere of the world’s first climate change opera, Auksalaq, which incidentally premiered on the same night that Hurricane Sandy hit the United States East Coast in 2012. The ensemble is a unique group of musicians and I’m really excited about the work EcoSono is doing right now.

You’ve brought attention to a number of regions and their struggles in the face of climate change, first the Alaskan landscape, and now the Atlantic coast. Where do you plan to bring listeners with your next project, and what do you hope they’ll learn?

My new work is about seeking situations where people are living in balance with the environment, even in symbiosis with it. I want to celebrate these points of hope in my music because I’m concerned that hope is in short supply for young people who are being asked to bear the long-term burden of an increasingly toxified environment in exchange for short term corporate profits they won’t even benefit from.

My music advocates for post-humanism, which is about decentering humans, broadening our sense of diversity and inclusivity to include biodiversity and geo-inclusivity. Like The Dreams of Seagrasses, imagining how the seagrass bed dreams of a coastal future, or the plaintive Crab Flutes, celebrating the domestic life of a fiddler crab, or in Oyster Communion, listening to a generational legacy of oysters who sequester carbon and protect the coast against storm surge; even with the softest of bodies they are multifaceted protectors of our coastal future.

These compositions are a cornerstone of SOUNDSCAPES OF RESTORATION. Humans need to stop imagining ourselves as weak villains in this environmentalist drama and rather become strong protectors. I’m making a soundtrack for post-humanism.

Should listeners be inspired to take action against climate change after hearing your work, what steps would you recommend they take to help turn the tide?

Reflecting on SOUNDSCAPES OF RESTORATION, a listener might consider the human-nature processes around them differently and look for ways to conserve aspects of nature. Thinking of things from the perspective of the animals and plants around us is a first step towards taking action. It’s also fun and mind-expanding to shift perspectives like that. I recommend taking on a project to work on, like protecting pollinators, cultivating indigenous plants, promoting renewable energy, reducing pesticides or other chemical use in your area, cleaning up and reducing trash, becoming vegetarian, reusing things rather than buying new things, etc.

Do a little research on the project you are interested in and learn what you can do locally. Talk to others about what you are doing and why you think it’s important. And of course, vote for the environment in local and national elections. None of this has to take much effort or money, but it could be transformative in restoring human balance with nature.

Matthew Burtner is an Alaskan-born composer, sound artist, and eco-acoustician whose work explores embodiment, ecology, polytemporality, and noise. His music comfortably crosses boundaries between environmental science and art, philosophy and acoustics, technology and body, and he is a leading practitioner of climate change music and ecoacoustic sound art. As a composer, Burtner seeks out contexts where critical issues of human/nature interaction are addressed, whether in musical contexts, other forms of media, scientific conferences, or political conventions. His music has been performed in concerts around the world and featured by organizations such as NASA, PBS NewsHour, the American Geophysical Union (AGU), the BBC, the U.S. State Department under President Obama, and National Geographic.